Writing About Another (Who’s a Public Figure!) Without Malicious Intent

Working and traveling with my boss was easy—easy, that is, compared to writing about him. Noam Chomsky, a man I call simply Noam, is a public figure, a world-renowned professor of linguistics, a lecturer and author, a critic of US foreign policy, an activist, and a teller of truth. He is also a private person. Therein lies the rub. In 1993 I took what was to be a simpler job working as Noam Chomsky’s assistant and office manager. I planned to stay only a few years, just until I finished a master’s degree and then left to work as a psychotherapist. When I burned out of psych studies after only two years, I decided to stay put for a while and focus on my writing. In 2012, having found personal meaning in my job supporting Noam’s work, and traveling with him to Italy, I developed a blog. There I published stories about our individual and shared journeys, and our unpredictable correspondence, scheduled visitors, and uninvited guests. We enjoyed twenty-four years working together befor...

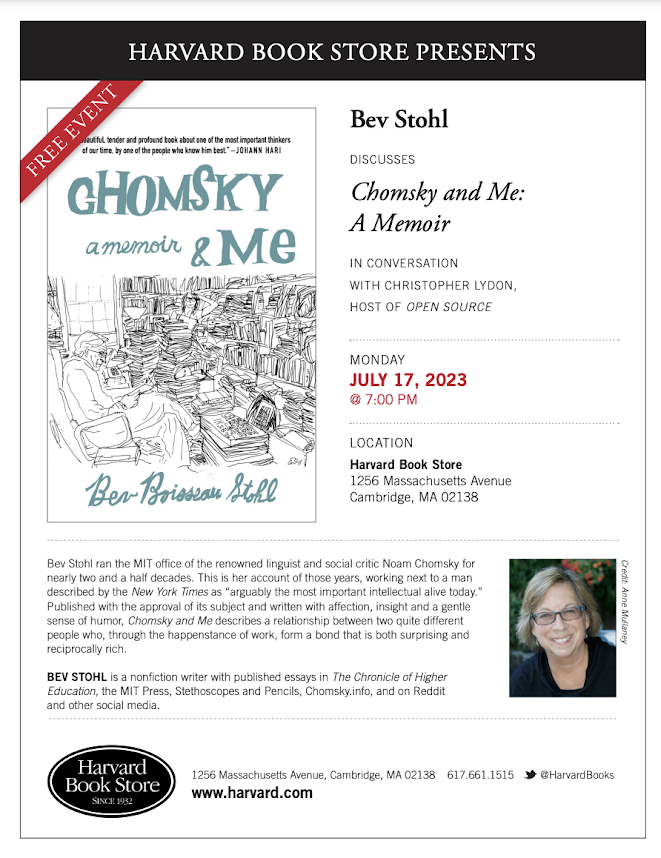

%20copy%20Watertown.jpg)